Since the 1970’s, a profitable trade has been emerging in the favelas, offering the poor a seemingly easy way out of poverty. This is the trade in drugs. Unfortunately narco-trafficking is not just illegal, and therefore does not help the integration of favelas into society, but affects the lives of each and every resident of favelas. As if the hardships of poverty were not enough, ordinary citizens live in constant threat of cross fire between police and the gangs, as well as between the gangs themselves.

The police have been known to use heavy-handed tactics when dealing with the drug traffickers. Yes, this is an understatement. Yesterday, the 10th of May 2003, police stormed the Morro do Turano, a favela in the North of Rio, and killed eight suspected drug traffickers in a shoot-out. They claim to have found guns and an undeclared amount of cocaine. Military police occupied the Mare, an area comprising 16 of the most violence-stricken favelas in the Northern part of the city.

In a separate incident the day before, the Office of Urban Planning was bombed early in the morning. The bomb was thrown at the entrance of the building as an act of intimidation.

In the past week the drug traffickers ordered some universities to close down. One university in particular refused to be intimidated and paid the price heavily: An innocent 17-year-old girl was shot by a passing car. She is likely to be paralysed from the neck down for the rest of her life.

The past 2 weeks has claimed the lives of over 100 people who have been shot dead by police raids on the favelas. Rio de Janeiro has slid down a spiral of violence that is affecting the lives of all its residents, especially those living in what were once referred to as “the leprosy of aesthetics infesting the beautiful mountains of Rio”.

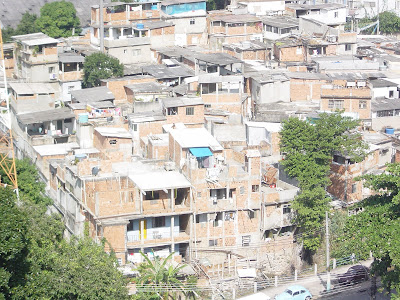

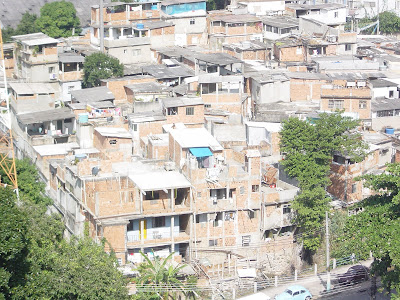

Morro do Borel

Rua Sao Miguel acts like the border between the favela of Borel and the Barrio of Tijuca. We meet our contacts Monica Santos Francisco and Gisella outside number 500 at 11:20am. We are 20 minutes late because of the diversion our taxi driver took us on to find a tape for my voice recorder This does not seem to bother the two warm and smiling young ladies who greet us with hugs and smiles, clearly happy that someone cares to visit their community. Monica works for the local municipality as well as a radio station I plan to visit after the weekend. Gisella is a social worker with the local Samaritan church. They both live on the morro do Borel.

Without wasting time we begin our climb up the steep road into the favela. On the first bend of the main windy road, already high enough to appreciate a good view of the city from above, five or six white policemen armed with long and narrow machine guns are standing around. I say white because later I realise almost everyone in the favela is Black or mulatto. Monica explains that over the past few days the police have occupied many favelas as the spiral of violence has intensified. Later I will learn what this means to the residents of this neighbourhood, one of the most violence stricken favelas of Rio de Janeiro.

As we walk past the armed men in blue, avoiding eye contact as I’ve left my passport in my flat, the road becomes heavily built-up on both sides. Monica tells me how since 1997 the local municipality has been implementing the barrio-favela project, aimed at turning the favelas into barrios. The tarmac road we are climbing is a consequence of this on-going project.

Monica leads me down this seriously narrow lane separating two houses just off the main road. A few meters down it leads to a space pasted with garbage, porch to a couple of single roomed houses, home to five or six family members. A little girl speaks into my voice recorder telling me her name and age. Her mother peers out of the curtain covering the entrance to the house, and greets us both. She is busy so we head off back up the main road. She had just been interviewed by representatives of IBASE, the NGO helping me find my way round Rio. Complete coincidence.

We walked past young teenagers tugging on kites from rooftops and off the side of the road. I ask Monica why these kids were not at school. She said she visited this particular kid’s home once in a while, and basically he did not want to go to school. I ask Monica why. She shrugs her shoulders. Monica points out the school at the bottom of the hill, across the road where the taxi dropped us off. It was built as part of the barrio/favela initiative: the teachers are badly trained and there are over 40 kids per class. Next to the school there is a huge supermarket, the French chain Carrefour apparently none of the favela residence can afford to shop there choosing instead the small shops inside their community. Next to Carrefour is a huge private school, much bigger and more beautiful than the government school. This and the supermarket stand out as symbols of exclusion, constantly reminding the people of the hill that they live in a world apart.

A little further up we stop at a nicely painted house with blue walls and yellow wooden shutters. Gisel tells me how she helped build this nursery with her bare hands a few years ago. It cost about 20000 reals or under £5000, donated by the church and collected from community intiative such as selling shirts and other products. We walk in and find a world apart, three stories high, painted with flowers, butterflies and filled with pastel colours that reflect the innocence and joy of child hood. It costs 50 reals per month to educate and feed a child. The teachers are all voluntary. When I learn that only 20 kids up to the age of 4 enjoy this loving and careing space, I ask Gisel how the children are chosen. “this is what broke my heart the most, having to turn down so many children. We chose those whose families were living in the poorest conditions.”

We leave this surreal space and continue our journey up the ‘morro’, deeper into the favela. As we progress further and further up the hill, the well tarmac road disappears, leaving a narrow path made of mud and soil, garbage, concrete, streams of sewage connected by a precarious net work of planks of wood. Monica explains that this area is not visible from the barrio and therefore was not included in the barrio-favela initiative. Here people are poorer, less educated, and pay much less rent. Giselle pays 200 Reals per month further down on the main road, compared to 50 Reals per month up here in the poorer area of the favela. Here the impact of a little investment and education smacks us hard in the face as we manoeuvre awkwardly across the path trying not to slip or step on anything we wouldn’t want to take back home. I ask Giselle why they don’t clean the area right outside their homes. “Getting people to live in favelas is easy, but the challenge is getting the favela to live in peoples hearts.” This world of dirt and ugliness is where people here wake up every morning. They are uneducated, neglected by the rest of society, left to hate the world they live in. I guess whether you are a child or an adult, if no one ever invests in you, it is very hard to gather the motivation and self-esteem to invest in yourself.

As we reach the top of the hill and begin our descent on the other side, the reverse contrast is apparent again: The road is properly built and there is a small pile of garbage nicely gathered to one side, as if left there on purpose as a symbol of pride and self-respect.

We visit another couple of schools for 4 to 6 year olds. There are only 3 schools in Borel, offering an education and a quality childhood to about 120 children. After that they have no choice but to go to a state school such as the one at the bottom of the hill. Monica explains how you cannot compare the love and attention given by the teachers of the community here in Borel to the impersonal job-like attitude at the state schools. This was clear by the pride with which the teachers and directors showed me around the classrooms, and brought my attention to every possible detail, from the painted walls to the books on the shelves.

One head mistress points out that the small wooden playhouse, which I noticed in other schools as well, is used to teach the children about the home. Many families are one-parent families due to either the father escaping the stress of family life in poverty, or the death of a parent due to a number of reasons. Playacting is a nice escape from reality into a perfect world.

As we continue our walk down the main road Giselle insists I visit her home. We take a step over the open sewers, which thanks to the lack of ‘activity’ and the relatively cool temperature do not smell too bad, and squeeze through an alley between two houses, into a small courtyard. The men sitting there greet us nicely, albeit with a subdued air. Very little eye contact is made. Gisella introduces us to her beautiful daughter who is there with Monica’s lovely girl, her husband and her tiny white dog. Gisella points at the moisture spreading at the corners of her ceiling, and tells me they will be moving out as it is becoming unbearable on the lungs. She coughs to make sure I have understood. She is one of the lucky ones who can move when at risk. One week from now the front page of the national newspaper has a picture of a couple of flattened houses due to a rockslide. An entire family is killed while sleeping.

I say goodbye and head off with Monica. Our next visit, the community music school, just across the road from Giselle’s. A large graffiti covering the wall ahead of us as we enter says “Borelouvando”, which is a play on words meaning ‘praise to the lord’. The drum at the centre of the picture says ‘Deus e fiel’, ‘In God we trust’. It occurs to me that faith in god was manifested several times throughout my journey so far. Through paintings on the walls of the schools and nursery, a church looking more like a community centre where people can gather and pray, the missionary centre housing several social workers, some even from abroad, and a large wooden cross looking over the morro from above.

Christianity might have been slow at protecting the rights of the blacks in the days of slavery, but at least it is doing a little to help pull them out of poverty today. Whether it is doing enough, I am in no position to say, but there is no doubt that the missionary workers are completely dedicated to helping, as they roll up their sleeves and work in the community clinic, help build a school or give hope and love through the ‘word of god’ in church, amongst many other social initiatives. The church offers people a pillar to gather around as a community, and generate hope, love and self- esteem. It also offers a safe haven for gang members looking for a reformed life away from the violence. Here religion certainly has a real and positive impact on the local community.

After making a bit of noise on a lovely drum we say goodbye and hit the road again. We have to beware of the motorbikes bombing it up the main road. Monica takes me to four black and white posters on the side of the road. On each one was a name and a profession: Thiago, mechanic; Carlos Magno, student; Everson, taxi driver; Carlos Alberto, painter. She explains that four days ago the police drove up the road we were on, shooting. She said they literally came into Borel and opened fire at whoever was in their way, and looked suspicious. “They shoot first and ask questions later”. The four young victims she said were innocent, one of them had come to visit from abroad. The police planted drugs and guns on them to legitimise what she described as a massacre.

I asked her why the police would do such a thing. She explained: “The police today are continuing the oppression of the military police in the late 1800’s. They were created to protect the elite. We are poor and black, descendants of the slaves, so they can come in here and shoot us whenever they want, and there is nothing we can do about it. The police have no respect for the people here.” Monica was clearly angry, albeit controlled and composed. As we continue our walk back, she points at some photocopied newspaper clippings to reminding people they have not been forgotten by the outside world. Further down is a notice saying the United Nations will be investigating the case, and is being looked at as a possible violation of human rights. A huge black flag hung across the street in morning, with the words ‘Podemos nos identificar’, a call for recognition. A man whose son was killed in a separate incident passes us by. He avoids eye contact.

The day after the shooting the people of Borel gathered together dressed in white, and walked into the streets below in protest. They demanded justice. Their call was heard by the president who sent in a minister on his behalf. He promised to investigate the case.

We bump into a friend of Monica’s who offers us a lift to the bottom of the hill. On our drive down Monica tells me: “There is no death penalty in Brazil, but the police impose the death penalty here in the favelas. If you live in a favela and you are black, you are condemned to death; by the police.”

.jpg)